-

-

Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced

From New York Times, 1962, James Baldwin -

-

-

-

-

Ultimately, the exhibited works each attempt to cement the ephemeral, to both identify and make concrete that palpable and transitory feeling of developing individuality amidst the context of shared struggle, when passionate optimism and collective sense of purpose overcomes collective dread. Each artist interrogates these interstices, with their own proposition for a way forward.

-

-

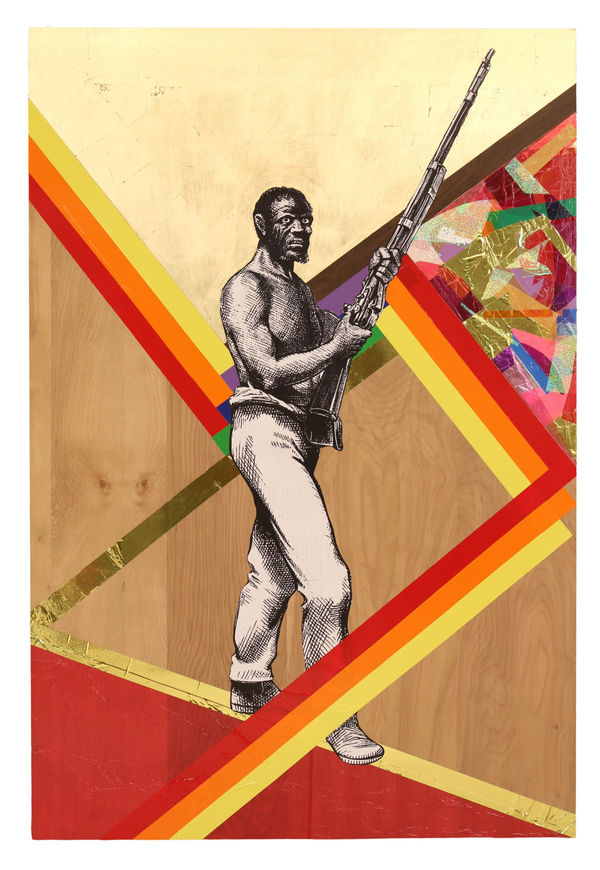

Delano Dunn, Far Back to Sanity, 2019

Delano Dunn, Far Back to Sanity, 2019 -

Delano Dunn, Green Rolling Hills, Nearest Thing To Heaven, 2017

Delano Dunn, Green Rolling Hills, Nearest Thing To Heaven, 2017 -

Delano Dunn, It's Not Far Down to Paradise, 2019

Delano Dunn, It's Not Far Down to Paradise, 2019 -

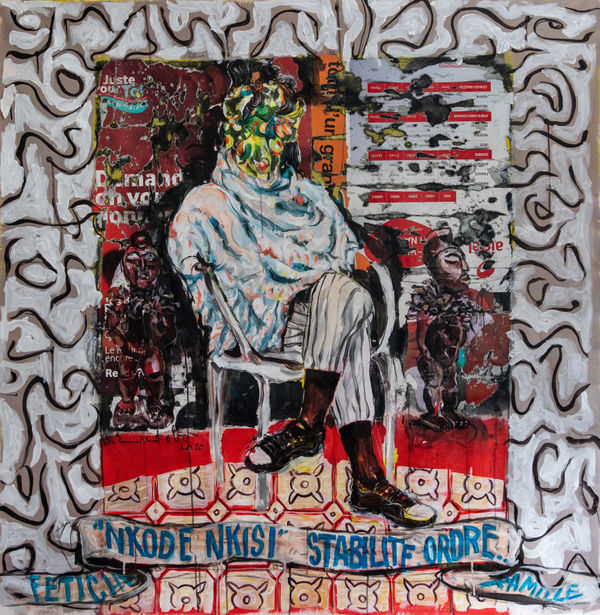

Bouvy Enkobo, Icône ya Masano, 2020

Bouvy Enkobo, Icône ya Masano, 2020 -

Bouvy Enkobo, Tingi-Tingi 1997, 2020

Bouvy Enkobo, Tingi-Tingi 1997, 2020 -

Bouvy Enkobo, Mokéngeli, 2020

Bouvy Enkobo, Mokéngeli, 2020 -

Shepard Fairey, Damaged Stencil Series: Natural Springs, 2017

Shepard Fairey, Damaged Stencil Series: Natural Springs, 2017 -

Shepard Fairey, Damaged Stencil Series: My Florist Is A Dick , 2017

Shepard Fairey, Damaged Stencil Series: My Florist Is A Dick , 2017 -

Thameur Mejri, I dreamt about Picasso nearly every night this week, 2013

Thameur Mejri, I dreamt about Picasso nearly every night this week, 2013 -

Thameur Mejri, Untitled (on off), 2019

Thameur Mejri, Untitled (on off), 2019 -

Thameur Mejri, Untitled (Drone 2), 2019

Thameur Mejri, Untitled (Drone 2), 2019 -

Paul Onditi, All Before Me, 2020

Paul Onditi, All Before Me, 2020 -

Paul Onditi, All Before Me 2, 2020

Paul Onditi, All Before Me 2, 2020 -

Beatrice Wanjiku, Realms of Existence II, 2020

Beatrice Wanjiku, Realms of Existence II, 2020 -

Beatrice Wanjiku, Restless in Rest V, 2020

Beatrice Wanjiku, Restless in Rest V, 2020 -

Beatrice Wanjiku, Restless in Rest IV, 2020

Beatrice Wanjiku, Restless in Rest IV, 2020

-

-

ABOUT THE ARTISTS

Delano Dunn both embraces and challenges the idea of “Black Utopia” - a time, place, and space in which America is an equitable and safe space for Black people, inspired by his childhood experience of the LA riots in the 1990’s.

Bouvy Enkobo provides a glimpse into the inner sanctum of Kinshasa urban dwellers and their search of identity within the all consuming urban environment.

Shepard Fairey investigates our endemic social issues, such as climate change and police brutality, attempting to elicit a collective sense of obligation.

Thameur Mejri attempts to deconstruct the relations of power and domination that structure contemporary societies, identifying in particular capitalism and the traditional ideologies that make them their instruments of control.

Paul Onditi continues to challenge our understanding of both our cultural topography and the physical world within which we exist, addressing universal themes of pollution, climate change, fragmented and unequal societies, and the degradation of our natural planet.

Kate Simon provides a moment of reflection with intimate portraits of reggae legend Bob Marley, whose eponymous album was the inspiration behind “Catch a Fire,” harkening to the power of music to provide the soundtrack for navigating social justice.

Beatrice Wanjiku’s vast canvases probe the human condition, delving into the psyche to question notions of reality and positionality to help us navigate in our social environment.

-

Current viewing_room

CONTACT

info@montaguecontemporary.com

+19174953865

HOURS

Thursday -- Saturday from 11am - 6pm

Private viewings available by appointment

Facebook, opens in a new tab.

Instagram, opens in a new tab.

Artsy, opens in a new tab.

Join the mailing list

Send an email

Copyright © Montague Contemporary 2026

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Please contact us to find out more about our Cookie Policy.

Don't Miss a Beat

Sign up for our mailing list to stay plugged in to the latest exhibitions, supper clubs, events, and news.

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.